“A man has to have goals – for a day, for a lifetime – and that was mine, to have people say, ‘There goes Ted Williams, the greatest hitter who ever lived.”

By Louis Addeo-Weiss, Brian Myers

When the discussion of the greatest of all-time is mentioned in baseball circles, the de-facto answer generally tends to be Babe Ruth, and with good reason. His career OPS+ of 206 is far-and-away the highest in baseball history, as well as his OPS of 1.164 and Slugging Percentage of .690.

By way of Wins Above Replacement (WAR), Ruth’s mark of 182.4 is the most of any single player. But as great as Ruth was, a lot of the criticism surrounding him and many-a-player of pre-1947, was the fact that Ruth, not something he could’ve avoided, played in non-integrated major leagues.

It wasn’t until Jackie Robinson’s debut in April 1947 that teams began to realize the potential of blacks in baseball.

Now, some seventy-two years after Robinson integrated the sport, the game has seen the likes of Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson, Joe Morgan, Ernie Banks, and Ken Griffey Jr. firmly entrench themselves in the hearts, minds, and record books of baseball fans and history.

Using the metric oWAR, seven of the nine top players by total career oWAR since integration are African-American.

Of the many great African-Americans, our game has seen, one can make a case that none, maybe other than Mays, possessed a skill-set and potential as did Barry Lamar Bonds.

By way of using baseball-reference’s database to access career leaders in Offensive Wins Above Replacement, or simply oWAR, Bonds career mark of 143.7 ranks third all-time, with only Ty Cobb (151.2), and the preceding Ruth (154.3) above him.

Now, being that Bonds played in an era where baseball was fully integrated, those unaware of his longstanding ties to performance-enhancing drugs would simply just dub him the greatest hitter of all-time, but it is his ties to steroids that leave many from crowning Bonds as the best-of-the-best.

So, to meet the criteria we have established, the best hitter of all-time must have:

Had a Hall of Fame-caliber career with oWAR exceeding 110

Played in a time when baseball was integrated

Played without suspicion of use of PEDs

Which leads me to believe that Ted Williams is an easy choice for the greatest hitter who ever lived.

Now, we can start with surface level numbers when discussing Williams. His slash line of .344/.482/.634 is impressive enough, but Williams also owns a career OPS+ of 190.

That 190 mark is good enough for second on the all-time list, trailing Ruth’s previously mentioned 206, and just above Bonds at 182, despite the fact that Bonds outhomered Williams 762-521, but that’s a conversation best saved for later.

Williams first four full-seasons, 1939-42, saw him do pretty much what he did for the entirety of his career, as he slashed .356/.481/.642, all within relative proximity to how his career numbers would shape out. Want to talk more about proximity? Williams OPS+ over that stretch of time was, you guessed it, 190, the exact mark he posted over his entire career.

Now, yes, these numbers are pre-1947, but unlike Bonds, there was never a mammoth increase in offensive output from Williams, as no speculation surrounding his performance following Robinson’s entry into the game.

In fact, if you compare what many felt to be Bonds’ best four-year run of hitting, 2001-2004, a time many felt was the peak of his drug use, the numbers are absolutely staggering.

In that frame of time, Bonds posted a slash-line of .349/.559/.809, hitting 209 home runs, amassing 44.4 oWAR, and a video-game like 256 OPS+, numbers, as great as they are, are indicative of someone playing with a chemical advantage.

For the sake of this argument, we can assume that Williams had a second four-year peak after the period of 1939-42, with the second one lasting from 1946-1949, where, in the midst of another historic run of hitting, Jackie Robinson debuted for the Brooklyn Dodgers of the National League, and Larry Dolby for the Cleveland Indians of the American League in April and June of 1947, respectively.

During this period, Williams slashed .349/.496/.642, while hitting a ‘pedestrian’ 138 home runs, 38.3 oWAR, and staying as consistent as ever with a 199 OPS+.

What makes WIlliams’ runs of hitting genius so fascinating is the fact that, in between the two rounds, Teddy Ballgame missed three full seasons (1943-45) due to his service during World War II, with many feeling Williams could’ve easily surpassed 650 home runs and 3,300 hits had he not gone off to fight overseas.

This, in no way, is a discredit to Bonds, but a reflection of just how different a player he was after questions started arising about the legitimacy of his numbers.

From 1989-1998, which wouldn’ve Encompassed Bonds ages 24 (turned 25 July 24, 1989) – 34 seasons, the Riverside, California native was still among the best hitters the game had ever seen, amassing 84.3 total WAR, higher than Ken Griffey Jr’s career mark of 83.8.

Bonds slash-line during this period was .299/.429/.581 with a 175 OPS+, a mark that still would tie him with Rogers Hornsby for sixth all-time.

From 1939-49, only eight of which could constitute as full seasons for Williams, he slashed .353/.488/.642 with a 195 OPS+ and a 72.6 total WAR. That mark could’ve been higher had Williams not broken his left arm during the 1950 All-Star game, limiting him to only 89 games all of that season.

Williams, too, would soon take another leave baseball to fight another battle overseas, spending nearly two years of active duty during the Korean War.

Even after these two separate four-year runs of elite offensive output, Williams production from 1954-57 would show that was still among the elite hitters in the sport.

The man they dubbed the Splendid Splinter posted a slash-line of .359/.505/.668 and a OPS+ of 203, but as great as that is, why is it important?

Two reasons:

The percentage of integrated players in the sport was seeing a drastic rise at this time, as we’ll soon see.

These were Williams’ age 35-38 seasons (though he turned 36 and 39 in August of 1954 and ‘58, respectively), a time where most players tend to seep further into their twilight years on the diamond.

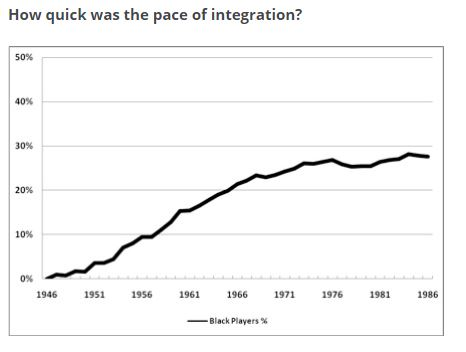

In regards to integration, let’s take a look chart courtesy of Mark Armour of The Society for American Baseball Research’s (SABR) article, Baseball Integration, 1947-1986.

The chart tells us about the drastic increase in integrated rosters during the mid-1950s, with the number reaching approximately 17-percent by the time of Williams retirement in 1960. Armory also makes it a point to note that these numbers don’t solely apply to African-Americans, as it also accounts for dark-skinned Latino player as well.

The last piece of information I’ll include in the case of the greatest hitter argument comes via a chart generated y co-author Brian Myers focusing on oWAR.

Myers’ chart notes that Williams average oWAR across 600-plate appearances, by most means, a full season’s worth of at-bats, of 7.75 is second all-time to Ruth’s 8.72, with Bonds placing seventh on that list at 6.84, and Willie Mays eighth at 6.57.

And while one could make a case that Mays could easily assume the title of greatest hitter of all-time, govern he frequently played against fellow greats of black baseball Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, and Frank Robinson, Mays’ career OPS+ of 156 is far-behind Williams’ 190 mark.

As for Bonds though, the last chart of Myers’ column is titled “Road?” Made to document the percentage of a players’ career where suspicion surrounding their alleged drug used persisted, and Bonds’ mark of 27-percent, which certainly highlights that period from 2001-2004, is the highest among all players on this list.

Sure, this may be a lot of numbers to wrap your head around, but what is for certain is that Ted Williams’ name is synonymous with hitting, and producing at the level he did when he did is enough for Ted Williams to merit the title of the ‘greatest hitter who ever lived.’